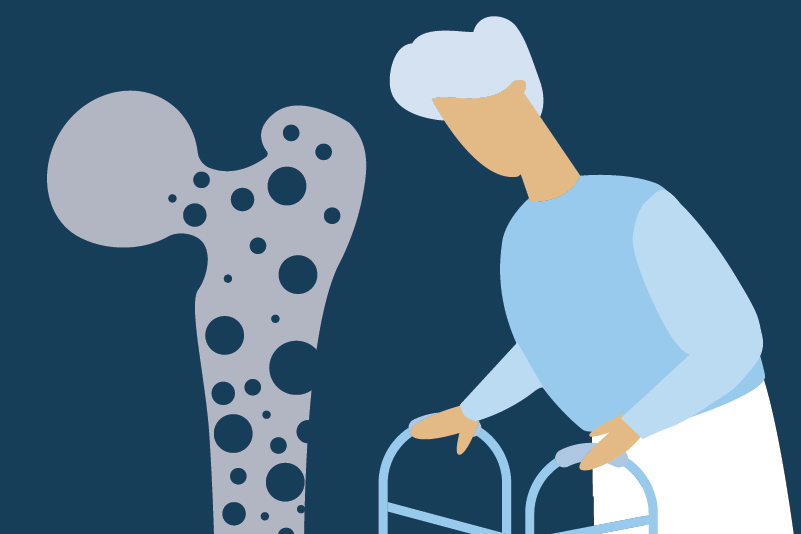

#44 Screening for Osteoporosis – Who Should Receive Bone Mineral Density Testing?

Reading Tools for Practice Article can earn you MainPro+ Credits

Join NowAlready a CFPCLearn Member? Log in

- Multiple risk factors had minimal value over age and weight alone.

- The OST based on weight and age was developed.

- OST performs at least as well as others.2-9 For example:

- OST performs moderately well identifying femoral neck osteoporosis (sensitivity 89%, specificity 41%) in postmenopausal white females.9

- Tools with fewer risk factors (like OST) predict osteoporosis as well as or better than those with more risk factors.3,4,7-9

- No tool was clearly superior.3,4,8

- Unlike other tools to assess the risk of osteoporosis, OST has been validated in both sexes and a variety of races.6,9

- There were a number of methodological limitations of included studies.2-9

- Recent reviews advocate for simple tools like OST.7-9

- 2010 Osteoporosis Canada guidelines recommend detailed history and focused physical examination for all patients 50-64 years, including assessment of 10 different risk factors for osteoporosis.10

- Time required to fully satisfy preventive recommendations is prohibitive.

- For example, physicians need 7.4 hours per working day for the provision of preventive services alone.11

- Multiple sites offer on-line or printable tables to apply OST.12-15

- Simple application of OST: Weight (kg) – Age (years).

- If <10, increased risk of osteoporosis and BMD is warranted.

- For example: A 55 year old woman weighing 70 kg has an OST=70-55=15,

- She is low risk for osteoporosis and does not need a BMD.