#190 Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): Is Perpetual Prescribing Inevitable?

Reading Tools for Practice Article can earn you MainPro+ Credits

Join NowAlready a CFPCLearn Member? Log in

- Clustered randomized controlled trials:

- Patients (n=196) taking twice daily PPIs for >8 weeks were randomized to receive information pamphlets with academic detailing for their physician versus standard care.1 At six months:

- 30% stopped PPI or changed to Histamine Receptor Antagonists (H2RA) versus 19% in control group, Number Needed to Treat (NNT)=10.

- Additional 50% reduced PPI dose.

- 113 dyspeptic patients randomized to receive a letter encouraging stopping/decreasing PPIs or usual care.2 At 20 weeks:

- 13% off PPI, compared to 5% in control group (NNT=13).

- Additional 9% reduced their dose.

- Patients (n=196) taking twice daily PPIs for >8 weeks were randomized to receive information pamphlets with academic detailing for their physician versus standard care.1 At six months:

- Cohort studies of patients on PPIs for >8 weeks:

- 73 Veterans with GERD attempted taper then stopping PPI.3 At one year:

- 34% switched to H2RA, 15% off all acid reducers.

- Older patients appeared more successful in stopping.

- 166 dyspeptic/GERD patients offered H. Pylori testing and treatment, then educated about symptoms, lifestyle and PPIs.4 At one year:

- 34% stopped, additional 50% reduced their dose.

- 27 GERD patients reviewed PPI use at periodic health exam.5 At 10 weeks:

- Ten (37%) stopped PPI: Six completely, four changed to H2RA.

- Of 97 predominantly GERD patients with normal gastroscopy, 27% stopped PPIs at one year.6

- 73 Veterans with GERD attempted taper then stopping PPI.3 At one year:

- ~60% long-term PPI users may not need them.7

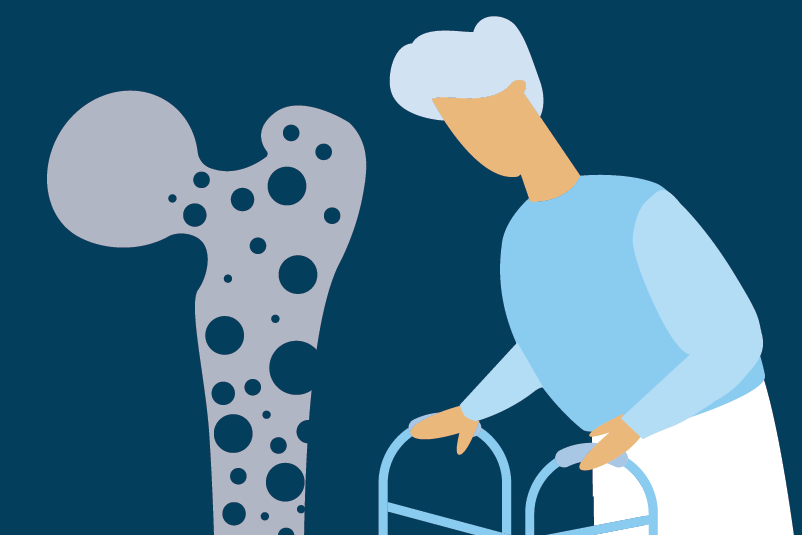

- PPI use associated with (but causation unclear):

- Clostridium difficile colitis:

- Community dwelling without antibiotics (1/10,000 risk)8 to in-hospital on antibiotics and PPIs (8-10% risk).9

- Fractures: Extra one in 2000 women over eight years.10

- Pneumonia.11

- Vitamin B12 and magnesium deficiencies.12,13

- Clostridium difficile colitis:

- Abruptly stopping PPIs may cause transient rebound GERD or dyspepsia symptoms.14,15

- Tapering may help.6

- Long-term PPIs should be considered for patients with recurrent symptoms, endoscopic esophagitis, complications from GERD (example: stricture), or those requiring gastroprotection.